By Celeste Bloom

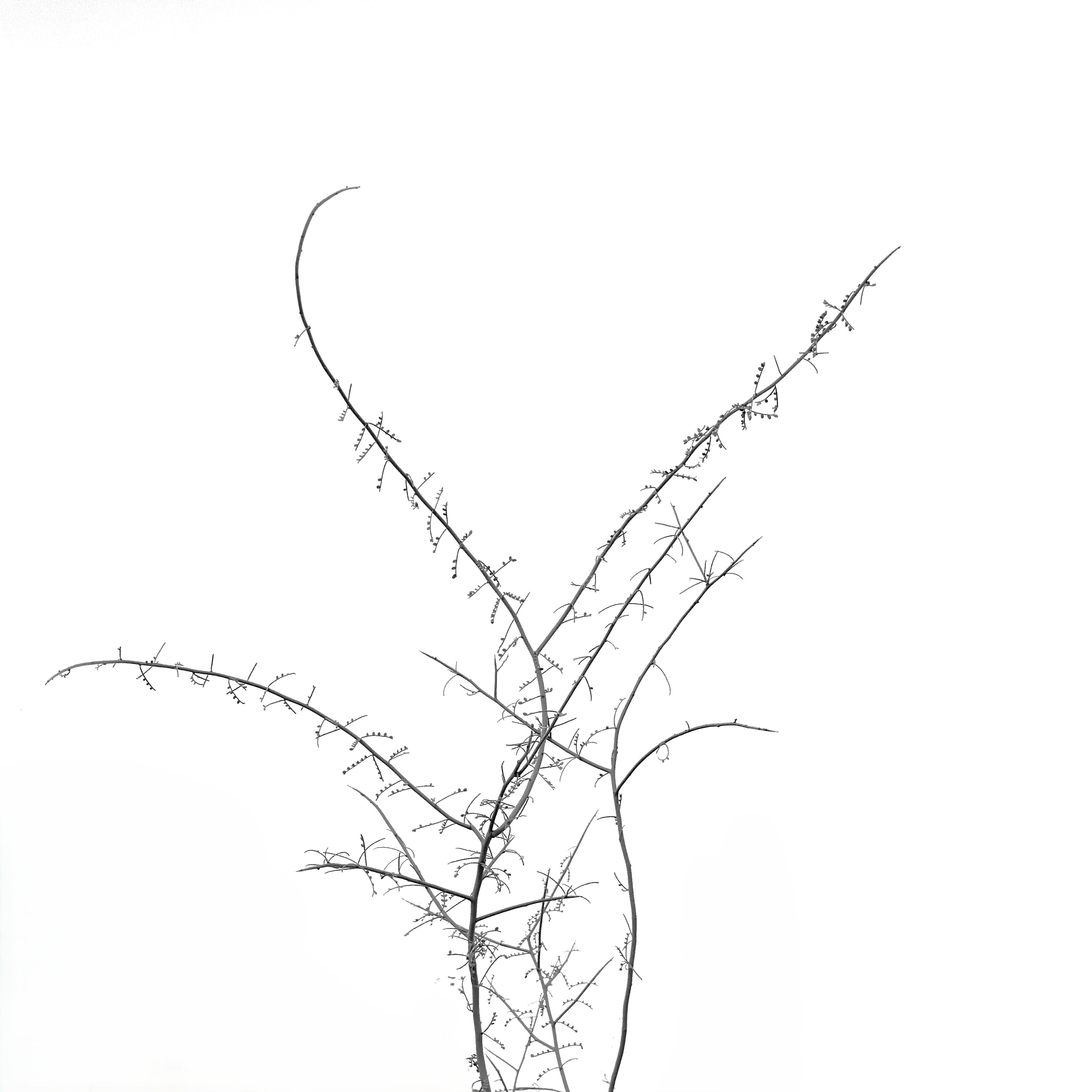

Sky Caged by Vishaal Pathak

About the Author

Celeste Bloom recently graduated with a BA in Literatures in English from Bryn Mawr College. She is currently based in Philadelphia, working as a college and career advisor. Her work has been published in The Write Launch, The Bryn Mawr Nimbus, The Haverford Milkweed Zine, and the Q&A Queerzine. They are also an editor for GLG zine.

About the Artist

Vishaal Pathak writes short stories and poems and occasionally clicks a picture. His photography has appeared or is forthcoming in Juste Milieu Zine, Moiramor, Ink In Thirds, and The Word's Faire.