By BJ Thoray

Alice couldn’t get herself to move out of the mirror’s gaze. She couldn’t tell if the dress worked. She sucked in her gut and ran her hand over her stomach. The girl was right. The dress was slimming, and she did look good. Besides, she’d still be one of the younger adults – proper ones anyway – at the event. These galas skewed old, and she still turned heads. Of course, the undergrads got the most attention, but often, they had little to say to the thirsty, wrinkled old men that craved their attention. Alice could hold their gaze and actual attention. The doorbell rang. She clicked the button.

“Yes?”

“Mrs. Albecht, I’m here to take you to the gala.”

“Thank you. I’ll be down in a minute.”

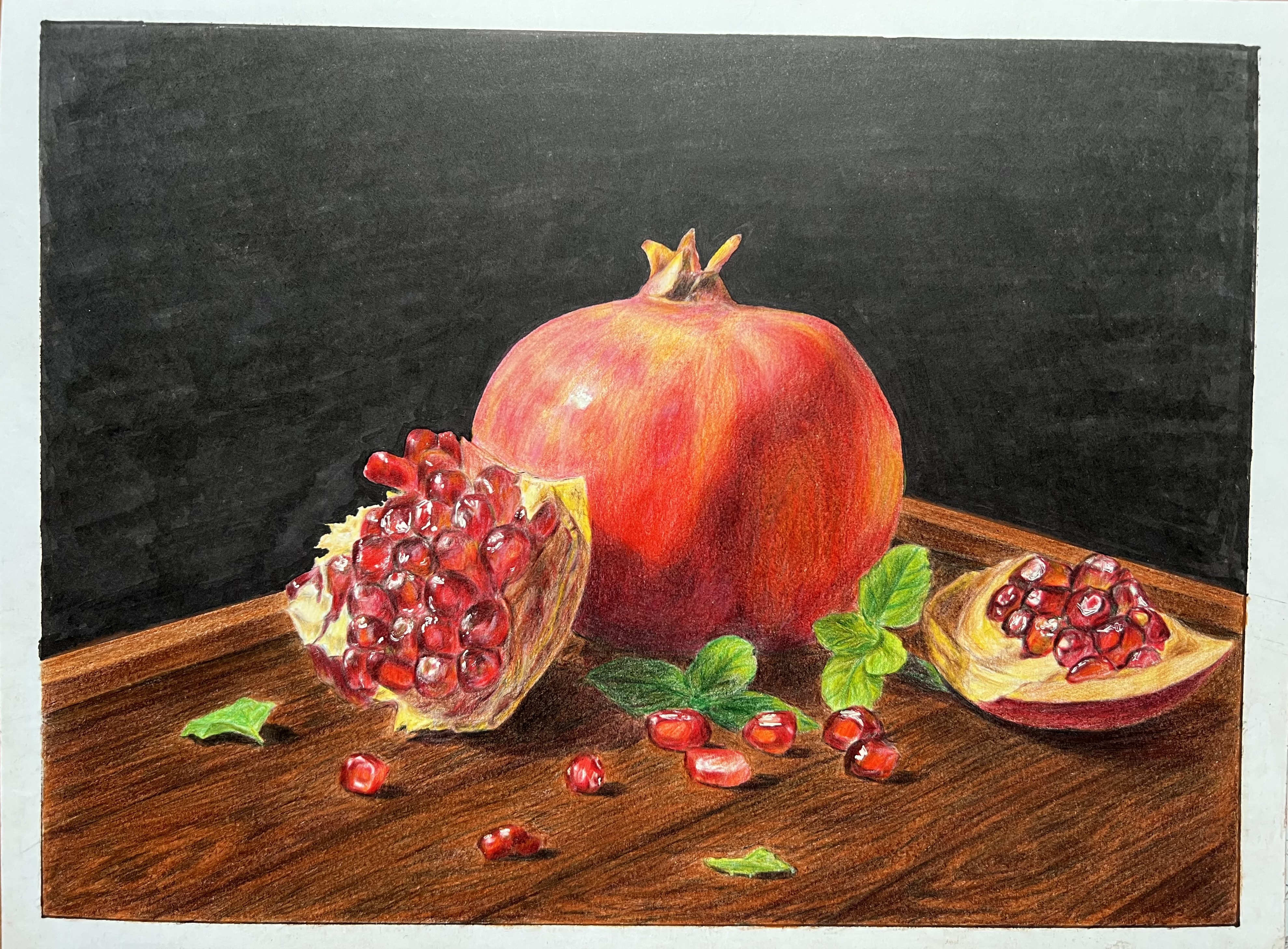

Still Life in Colored Pencil II by Éloïse Liu

She turned away from the mirror, picked her clutch off the bed, and checked her items. She was ready. If only Will and she were going together, but she knew it was a busy time for the department and that his work – mainly an opinion article on a partisan blog – was piquing interest again. His work was important for both of them. He worked on an important area – that was what had brought them together – and her understanding of his work and his need to do it was what had, in the end, forged their life together. Still, she hated making the entrance alone.

“Do you work for the department?” she asked from the backseat as the handsome young man looked ahead.

“In a way,” he said. “I’m working on my thesis.”

“Oh, my goodness,” Alice said, suddenly embarrassed. “And you’re taking time out to drive me? That’s not part of your duties.”

“Just a favor to Professor Albecht. I mean, the department asked me, but obviously I’m happy to do it.”

“Well, thank you. I’m sorry you had to come all this way.”

“It’s no problem. Besides,” he paused, “maybe the old guard will go easy on me come defense time.”

“I wouldn’t count on it,” she teased. “They play hard, and they work hard.”

“Did you have to defend?” he asked.

“Oh yes, ages ago. I was a wreck for weeks before. Then I got married shortly after, and now it’s like it was another life. What’s your name?”

“Timothy, Tim.”

“Well, Timothy, I’ll make sure to tell the professor what an impressive, promising thinker you are.”

“Oh, no. Please don’t,” he said. “Professor Albecht hates brown nosers.”

“Ah, so you know him well,” she laughed. But not if they get far enough up there, she thought.

He drove through the parking lot and stopped in front of the conference hall.

“Oh, I’m supposed to meet William at the department lounge,” she said awkwardly.

“’Fraid not, Mrs. Albecht. They told me they were headed here. Said I should drop you off at the ceremony.”

“Oh, um, okay,” she paused. “Are you coming inside?”

“Have to park and help clean up in the department building, but I’ll be there later.”

Still Life in Colored Pencil I by Éloïse Liu

She opened the door and stepped out. People, no one she recognized, were filing in. Most were older and well-dressed, the more eccentric ones festooning their formal wear with little tics – a hat here, a larva broach there, ribbons with noble causes, neckties with subversive messages – and most of them couples. Alice felt self-conscious as she stepped up the broad stone stairs. She paused in the lobby and pulled out her phone. There were no messages from William, no notice that there had been a change in plans. She looked up for a second.

“Sparkling wine, ma’am?” a voice called. A lonely-looking young man and a geeky young woman dressed in caterer’s attire were standing behind a table lined with champagne.

“Thank you,” Alice shot back. She put her phone back into her clutch, strolled to the table, and smiled at the pair as she took a glass. Comrades, she thought. At least someone else is uncomfortable.

Alice strolled into the ballroom, nodding at the security guards as she entered.

“Mrs. Albecht,” one said and nodded as she walked past. The college wasn’t that big, but if they’d asked for her invitation, she would have been happy to call the good professor and get him to sort it out. Assuming he wasn’t there inside already.

As it turned out, he wasn’t, but Betty Johnson pulled Alice into her orbit.

“Alice, how are you?” Betty asked.

Alice scanned the room for her errant husband.

“Oh, just wonderful, Betty. How’re you?”

“Fantastic. How’re the kids?”

“With the sitter tonight, thank God. Yours?”

“Oh, well, Horace is getting all the grades again. Guess the apple doesn’t fall far. Where’s Will? I thought you two would be coming together.”

Alice tried not to frown. “Me too. We planned to meet at the department reception, but I guess they wrapped early. He arranged my ride and then changed it to come here.”

“I see. Those receptions are so wishy-washy. It’s just pre-gaming for academics.”

“And Charles?” Alice said changing the subject, “Is he with you?”

“Oh, he’s somewhere, making the rounds,” Betty said.

Laughter boomed from the entrance, a mix of deep, loud chuckling and a more high, shrill tone. There he was, Professor William Albecht strutting in with the department stragglers, his fellow professors and a select group of grads. Timothy, her driver, wasn’t among them, but William’s teaching assistant, Sylvia – young, thin, with curly hair and wide eyes – was walking just behind William and Professor Gorne. She was looking at William and laughing at his side, her eyes focused on his cheeks. He brushed a strand of gray from his eyes back into his salt and pepper mop. He was a man holding court. Alice stood next to Betty, waiting for William’s focus to turn, for the spell of the boozy department reception and the excitement and the fashionable lateness of it all to break and for him to look firmly ahead at her.

When it happened, he put on a big show.

“My love!” he shouted, running to her.

It was loud and enthusiastic but also off. At first, he sounded too drunk. Sloppy or overeager in a way that rang false. He kissed her on the lips (a loud exaggerated peck) and hugged her. While in his embrace she was straight in the face of Sylvia, who had followed him right up to his wife like the little lap dog she’d become over the past semester. She too had on a black dress, a smaller one that started lower and stopped higher, with a thin, wispy chain and charm that swooped around her chest. Alice now felt self-conscious about her neckwear, a bulky multi-colored necklace that was too different, or ethnic, to be casual. Alice pulled away.

“How was the reception?”

“Early. You know, a bit after lunch, we all kind of were done for the day, so we lingerers had a quick drink. And then since Tim was picking you up and it was getting late and we’d already finished the reception stuff, we figured…”

“Right. Timmy mentioned. I just assumed you were already here.”

“Have you been waiting long? I’m sorry. We—”

“It’s okay. I was just talking to Betty.”

“Yeah, we should’ve been here sooner but someone,” he said, his eyes shifting to Gorne, “wanted a smoke and that turned into a whole thing, and you know how it is wrangling these animals.”

“Such smart people.”

“Smart is difficult,” he smiled. There was that charm.

Suddenly William’s arm was around her, and Alice was surrounded. To her side was Betty, now joined by Charles who’d either finished his rounds or flocked back at William’s grand entrance. Next to William was Sylvia but also Professor Gorne.

She could be next to Gorne, Alice thought, but she’d rather be there. Close, just a breath, just a hair away from her husband. Alice’s morose spiral was interrupted by a sharp harangue of laughter. It cut through her edge.

“And how old are they now?” Charles asked.

“Eight and six,” William said. “Feels like yesterday, doesn’t it?” He squeezed Alice then turned his head and smiled eagerly.

“He says that, but he’s not the one at home all day,” Alice deadpanned. “No, but seriously, it’s true. Time. Just. Flies.”

“Tell me about it!” Betty cried out. She launched into a thinly-veiled account of her boy’s most recent achievement, but Alice zoned out and began stealing looks at Sylvia. Alice had worn Sylvia’s dress before, years ago, the same design or one so similar that the differences (manufacturer, retailer, material) were moot. Alice felt heavy and weighed down. The change in initial venues had unsettled her practiced excitement for the event. Part of her had been dreading it. Too much time with you-know-who. Too much time in that awkward space and place where you’re being watched and trying not to react to things that must be apparent to everyone. When William came home these days, she couldn’t help but resent how much of his excitement was beyond the house and the life they shared. The missed reception had let that seep into tonight.

“Do your boys play any sports?” Betty shot at Alice, who fingered her bulky necklace, unable to stop drawing attention to it.

“They take swimming lessons, and Bradley does soccer,” she responded.

“I thought it was the other way around,” William chimed in.

Alice grinned, looked him straight, and said, “Not so, genius.” It was a coy look with delivery to match, and the circle erupted in laughter. This was a show that they knew how to put on, which wasn’t to say it wasn’t real. They were good at this. Had that banter. They buzzed. He was the roguish wildcard. She was the serious one. It’d not been this way at their start.

“You’re empty,” William said. “Wait here.”

“I’ll come with,” Gorne said. They peeled off, and Alice saw beyond the circle at the rest of the faculty and grad students that had congealed around the initial circle. But in her immediate face were Betsy and Sylvia.

“Oh, are you with William’s department?” Betty asked.

“Yes, I’m Will’s—Professor Albecht’s TA,” Sylvia replied.

“Oh, so you’re a young researcher making her way through,” Betty said.

“It’s a great department,” Sylvia said. “I’m very lucky.”

Alice’s eyes darted to Sylvia. She stole a glance at her knees.

“What’s your specialization?”

“Oh, um, you know, I’ve kind of been drifting between a few things, but I want to take more of a tech focus. I’m just not quite sure what that means right now.”

“Uh huh, well, if that’s what you’re interested in, I can certainly see why the professor is your man,” Betty said. Alice winced at her choice of words and hoped no one noticed.

“He’s so brilliant,” Sylvia said, shaking her head in awe. “And it’s all so interesting.”

“Alice actually came through the department as well. Isn’t that right, Ali?”

She snapped to. “Yes, absolutely. It’s a fascinating subject.”

Betty leaned in so just the three of them could hear. “That’s actually how they first met,” Betty said with a mischievous smile.

“It’s true,” and then a pause, “…but it was very above board. All professional and platonic until well after my thesis defense,” Alice lied. It hadn’t been public until after, or, more accurately, it hadn’t been overt, but it had been a long time ago. It was a different time.

The men returned in guffaws and hahas, each laden with multiple flutes of drink which they distributed far and wide until they each only had one.

“What’s the word? What’re you all talking about?” William asked Alice even though he was looking at Sylvia.

“How we met, actually,” Alice responded.

“United by our love of knowledge. And culture,” William beamed.

“I’ve heard so much about you,” Sylvia said. “It’s nice to finally meet in the flesh.”

“That’s so sweet of you,” Alice said. “I guess I should thank you for helping clear some things off this one’s plate.” She patted William’s arm and worried that this moment – her saying that – would keep her up through the night, personal betrayal personified. “Gives him more time for our children.”

“I think this one’s going to publish within the year,” William said gesturing at Sylvia.

“How lovely,” Alice said. Funny about that, she thought. He’d said something similar at a similar sort of event about Alice when she was one of his. Then and there, his then-wife wasn’t present. She didn’t attend. Their divorce wasn’t long after. Alice hadn’t known Dinah well, and they’d had few meaningful conversations, if any. But they did have a talk, a mostly one-sided one, and sometimes though she tried very hard not to, Alice still recalled things Dinah had said to her. The observations. The implications. Even the angry, ridiculous little snipes that the wronged or manic or those abutting instability can’t resist. She didn’t remember all of it, but she remembered enough when she least wanted to.

“Sorry, there’s someone I must say hello to,” William said and walked off, leaving them face-to-face. If he was hiding something, he certainly wasn’t afraid of it being found out.

“And what was your thesis on?” Sylvia asked.

Alice paused then said, “So are you from the state?”

Sylvia was unfazed by the elision. “Yes, from a small town. It doesn’t feel like the same state, really. Are you a native?”

“I wasn’t. But obviously when we married, I moved. I’m originally from out west. But this is now mostly it for me.”

She looked down, taking in Sylvia again. She scanned her knees for discernible marks just in case Sylvia was prone – as Alice had been – to helping William pick up whatever he’d clumsily dropped under his desk.

“Do you ever go back?” Sylvia asked.

“Of course. You know, we take the kids to visit. Or we go and visit the relatives and sometimes William meets us. It changes so much, but it’s still home, I guess. In a way.”

“How do you mean?” Sylvia asked genuinely interested.

“I mean, you can’t go home again, but you do. But now, with kids, it’s kind of like where you raise them is home.”

“So, this is your home?”

“The one I chose,” Alice said suddenly steely and narrow-eyed.

“I’m a bit of a rover myself,” Sylvia said. “I struggle to settle.”

“That’s a good way to be,” Alice said. “Healthy, right?”

“The way some of these women talk, you wouldn’t think so,” Sylvia sighed.

“They want you to make the same choices they did so they won’t be tempted to have regrets,” Alice said.

“Wow…that’s so true. You’re like my spirit animal.”

“Excuse me,” Alice said as she gulped the last of her flute. “Oh, would you like one?” she asked as she craned her neck over the drinks table. Sylvia wasn’t listening. She’d already turned and struck up another conversation.

Still Life in Colored Pencil V by Éloïse Liu

Alice walked to the table. She looked at her feet as she walked and felt flushed and fatigued between the wine, the atmosphere, and the sense that her every reaction was trial by fire. She picked up a glass, moved to the side, leaned against a pillar, and sipped. She studied the department with its collection of boozed professors and grad students humoring them. The corner of her eye locked on William as Sylvia as he subtly but surely moved closer to her with each comment, each shift of weight, each movement to widen the conversation circle until they were chatting exclusively.

It was a mirror, Alice knew. Deny it all she might, she couldn’t totally lie to herself. Maybe it had been a kindness that Albecht Wife #1 didn’t show after the physical part had begun. Alice had reserved a point of pride that nothing untoward had been shown to her. It was all deduction and innuendo. There had been no walking in on acts. No opening the door to find two people quickly extricating from each other. No ribald messages or sloppy moments of passion caught out. Alice had been responsible yet now she felt that despite those measures of grace, if what was happening was indeed happening, then those courtesies weren’t being extended to her.

The tone of William’s voice had come under control as the department reception version of him ceded to this new version. An opposite reaction now seemed to grip Sylvia, whose cautious quiet was in oblivion – she laughed at something William said, and her laughter boomed through the room. She pulled a strand of hair back behind her ear. Her eyes, Alice thought, were as big as saucers hoovering up every detail of her husband.

“Taking it all in?” Betty asked as she joined with Cecile, the endlessly elegant French wife of the department chair.

“Sometimes I just need a break…from the department,” Alice said.

“They’re quite the band, aren’t they?” Cecile grinned. “Sometimes being in the middle, it just feels like noise.”

“Couldn’t have said it better myself.”

“Oh, well you know, that reminds me about Horace’s teacher…” Betty chimed in.

Alice’s gaze drifted back to them, careful to avoid any furtive look or sense that she was peeking. She turned to the couple but appeared as if to be just taking it all in. As she looked at her husband and his TA, surrounded by the department but blissfully unaware, she knew what parts of Sylvia so enchanted her husband and she knew exactly how Sylvia felt now: as if she was the only genuinely interesting person in the world. It was his attention to her in spite of their stimuli-filled surroundings that were intoxicating. They looked natural. They looked happy. Did it matter that he’d promised Alice that this, leaving for something better, wasn’t a habit?

“I’m not one of those men,” he’d assured her when he first floated the idea of going away together. It was a transition, from passionate, reckless animals to an item. It would be a few months more before he suggested that he wanted to be happy.

“For real this time. We got married young. She just doesn’t want to be in my life in the same way,” he’d explained. Alice then was the rebel – sexy, wild, and unsparing – to his buttoned-up, hemmed-in, tweed-wrapped academic insisting on his professional relevance like a little boy in adult trousers.

“Your Horace must be something,” Cecile cut in finally. “Alice, are your children’s teachers as…interesting as Betty’s seem to be?”

“Ugh, I can’t say,” she deadpanned. “Being married to a teacher, I try to limit my time with them. That’s a joke.”

“I was going to say I agree,” Cecile said. “They never leave it in the classroom.”

“Or the teachers’ lounge,” Betty laughed. It was loud and performative, on par with Sylvia’s. No one turned. No one looked. The heaviness was on Alice as she flailed for something to add. It occurred to her that she was now just getting the bill for a very expensive meal that she’d consumed and assumed had been organic. It felt easy, comfortable, natural. But not cheap. Now the wheel had turned, and she couldn’t shirk the feeling that she was learning about a previously undisclosed part of a system she had inadvertently entered years ago. Time, love, family, none of it had been payment enough. At the end of the meal, you still had to be taken back behind to wash dishes. She gripped her clunky necklace.

She closed her eyes. When she opened them, William and Sylvia were right there.

“There you are. We were waiting for you to come back but then you didn’t, so we thought we’d join you on the pillar.” He flashed the smile he used when he knew he was being cute.

“Oh my god, William was telling me about your seasonal recipes,” Sylvia said.

“The summer salad, the winter soup,” William trailed off.

“He said you’re the one to thank for keeping him fit and fed,” Sylvia said.

“You know what they say about the way to a man’s heart,” Alice finally wedged in. She was sure she knew this game. They were talking around her, not to her. She was their conduit. Alice felt as if she was sinking into the ground. “Love, can you get me another?”

“Of course,” he said, looking at Sylvia and raising his eyebrows. “Be right back.”

Sylvia turned to face her.

“Excuse me,” Alice said, “I need to freshen—er, piss.”

She didn’t wait for a response. She strutted to the toilet, exuding confidence and staving off what felt like a panic attack (Hello, old friend.) She stepped higher, convinced that the carpet was quicksand dragging her down deeper with each step. She calmly entered the washroom and stopped at the sink. Alice peered into the mirror and deep into her face. All she saw were cracks and wrinkles. As gentle and minor as they were, all she could see was gauche, clumsy daubs on the face of a clown.

The necklace shifted and knocked against her clavicle, and she peered into it and down what was now clearly the conservative neckline of a yesteryear dress worn by wives becoming secondary to mistresses. She fumbled with the necklace then pulled it forward without thinking and choked herself. She stared into the mirror and grabbed it tighter, twisting until her breath sputtered and wheezed then stopped. Not another cent of life could squeak past. The thrill of those tender, illicit first moments flooded through her. She looked up, her eyes caught the light, and she sneezed. She wanted the necklace off. She lifted it then reached for the clasp.

“Do you need some help, dear?” an older woman asked.

“No, thank you,” she said and smiled. She stopped and went through her clutch, took out lipstick, and started to apply. Once the other woman had left, she pulled the heavy end of the necklace up and shimmied it up around her head then over. She laid the clasp side down on the counter, lifted her lower leg, grabbed her heel, and used it to smash the clasp and chain. The damage wasn’t confined to the area. She returned the heel to her foot, clutched the necklace in hand, and left the bathroom as a toilet flushed.

When she returned to the hall, William and Sylvia were back with the rest of the department in their merry clump. William and Sylvia were, of course, next to each other though they looked to be in the middle of a wider conversation. Sylvia was the first to notice her as she approached the circle, but William was the first to notice the necklace.

“What happened?” he asked, all attention shifting to his question.

“The clasp broke. I don’t know. It just fell off while I was freshening up. Can you…?

Without waiting for him, she leaned forward and slipped it into his coat pocket. She leaned back and flashed a smile.

“Where’d you get that? It’s a very unique piece,” Professor Gorne slurred good-naturedly at her.

“A souk in Tunis,” she said. “Ages ago, you know. I wasn’t going to bother, but this vendor was selling things that you didn’t see everywhere else, and then she offered to take me to the workshop. I thought it was a scam, but then it just led to this crazy day. But anyway…”

“Oh, wow,” Sylvia said.

“What happened next?” Gorne slurred, eyes twinkling.

About the Author

BJ Thoray is a writer/editor active in the nonprofit and content creation spaces. BJ’s stories have been published in The Aesthete, Forum Literary Magazine, Rundelania!, Black Cat Press, and Kosmos Obscura. Originally from California, BJ is currently based in Belgium, less for the waffles, more for the surrealism.

About the Artist

Éloïse Liu is an artist from High Point, North Carolina, although she thinks of herself as a citizen of the world since she has lived in thirteen cities, five countries, and three continents in her adult life. She drew and painted from a young age and has won art contests at city and state levels. She was also featured at the local public library as artist of the month. She likes to draw and paint in a variety of mediums, but her new favorite is colored pencils.