By Jonathan Mann

Bury my heart with the artichokes, Grandad says, peeling open his chest so his granddaughter can reach in. Understand that she’s the type of girl who steals her mother’s Sharpies and draws Barbies on boys’ white Nikes when they’re not looking. She’s never been given a more serious request, so she follows Grandad’s orders to a T, cupping the clogged heart in her small hands and planting it by the artichokes and in between the tomatoes and cucumbers in Grandma’s garden. My heart’s only going to get smaller if it remains in me, he explained, which is why you must plant it.

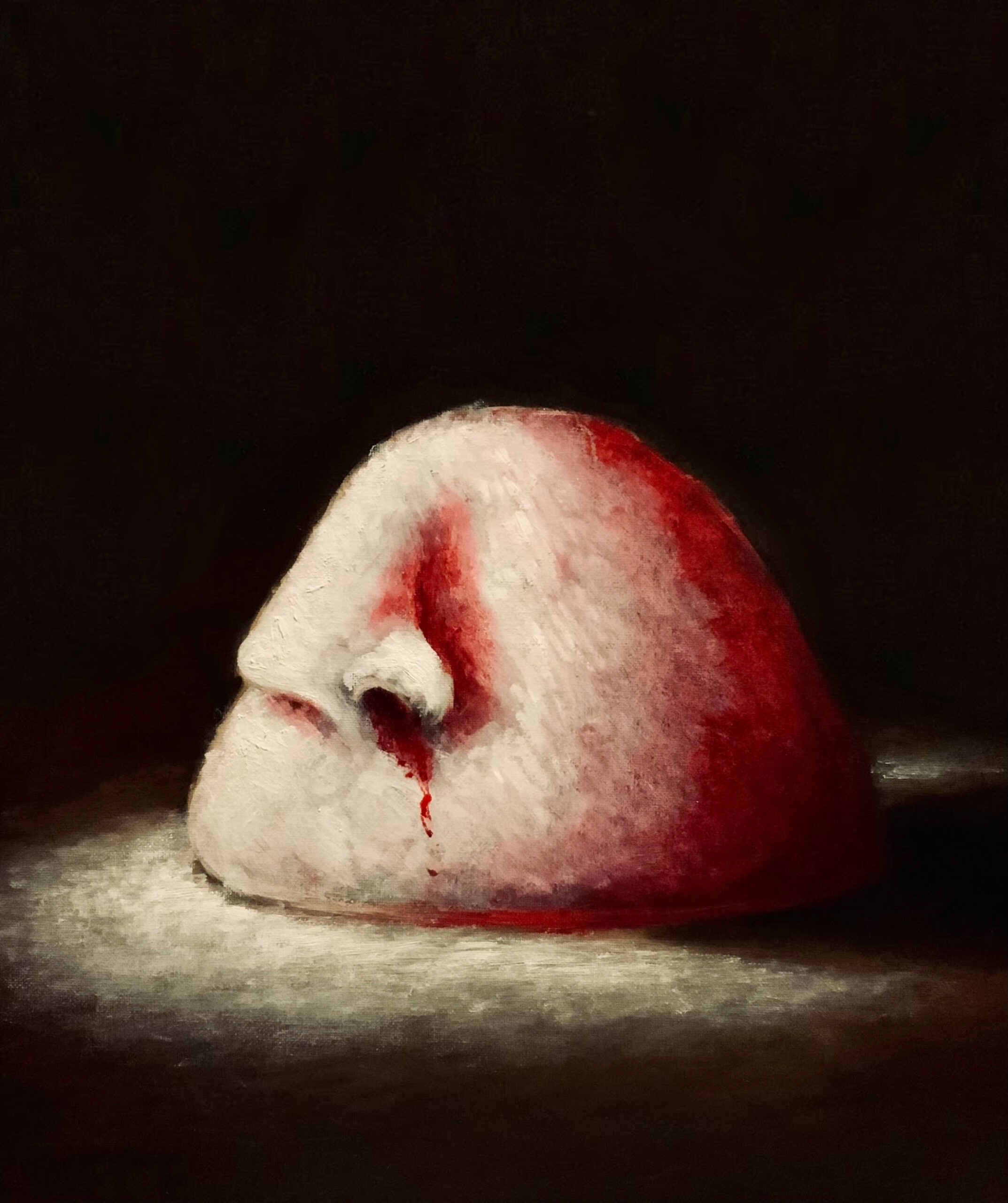

When she returns to visit Grandad, he asks her to place his eyes atop the oak fireplace mantel next to the family photos in gold dollar store frames. He hands her a silver surgical spoon, and after she scoops out his blue eyes, she places them in perfect view of where the ladies of the family will have tea on Tuesdays and where the grandkids will tear red wrapping paper on Christmas. Before long, the granddaughter realizes Grandad is falling apart, and when she begins to question her actions, he reassures her that she needs to disperse the pieces of him around the house like a pirate’s treasure.

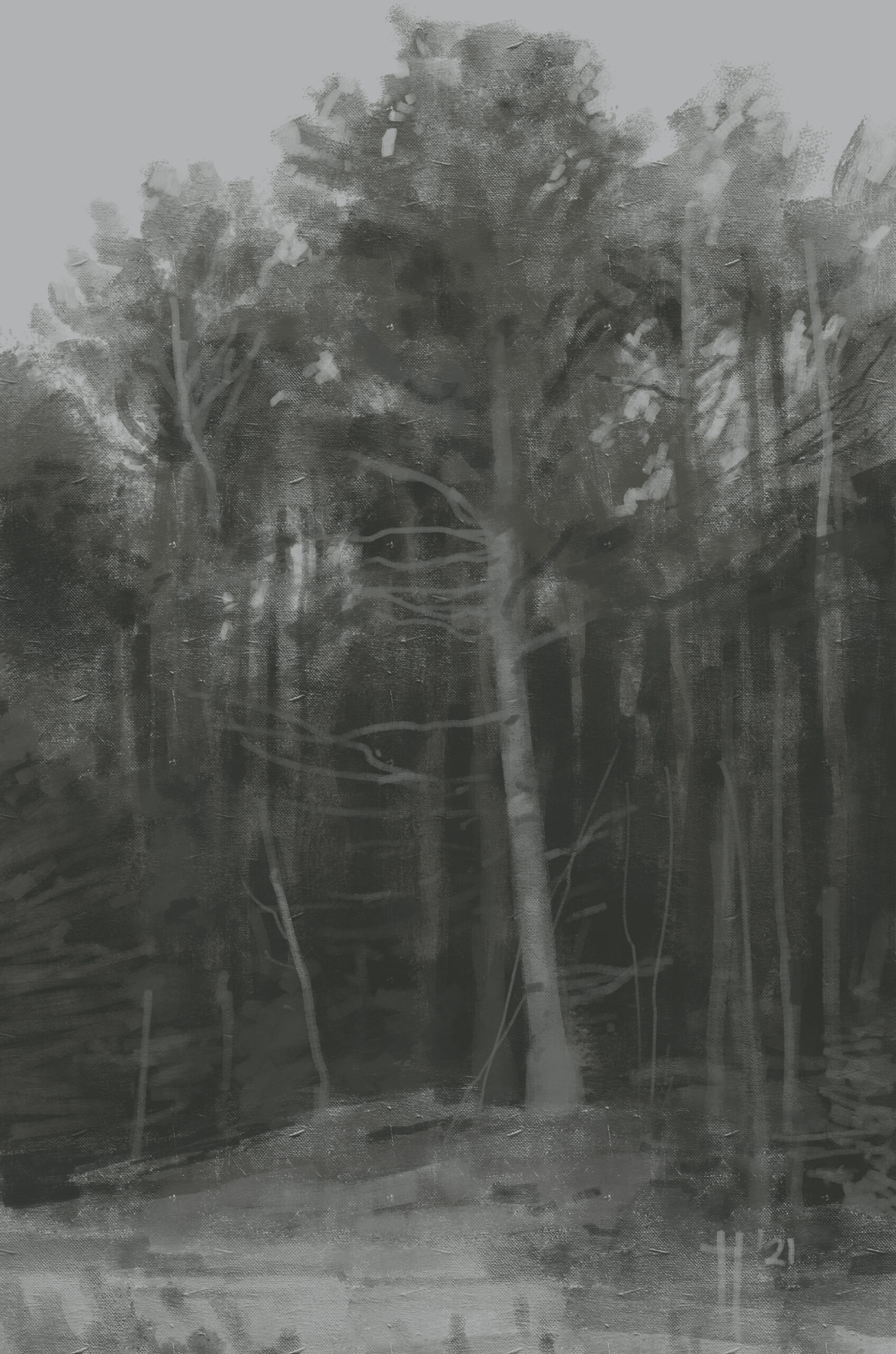

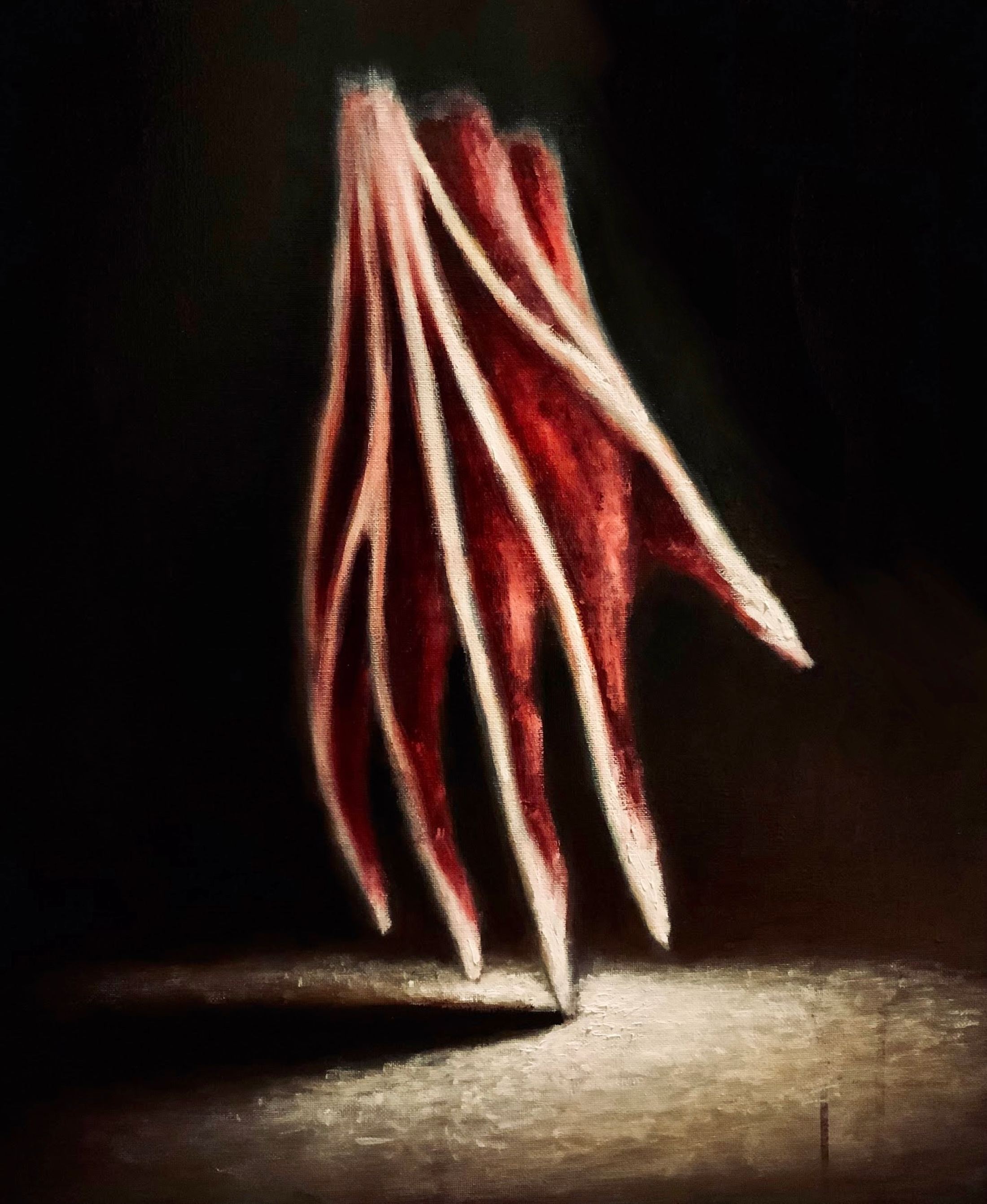

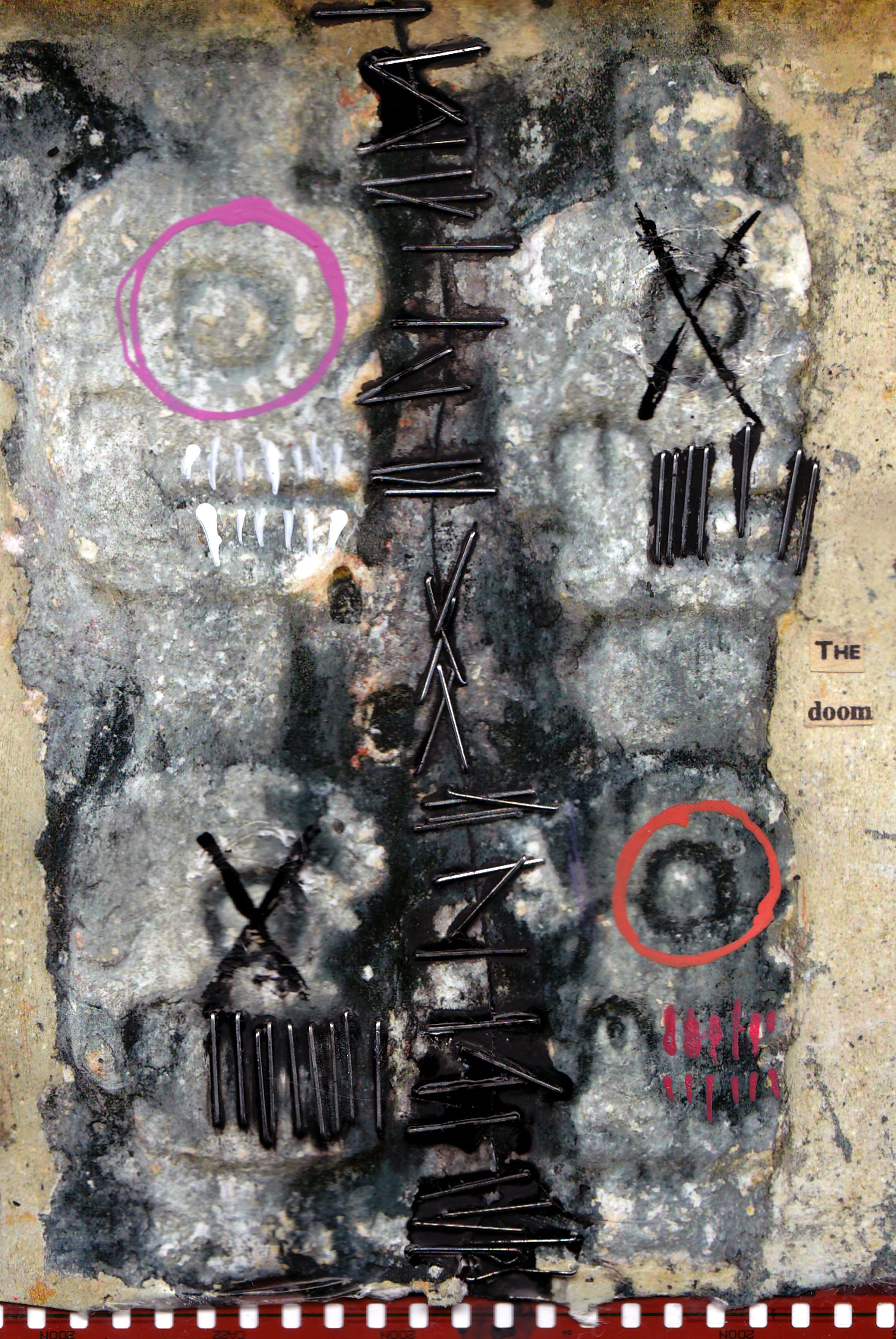

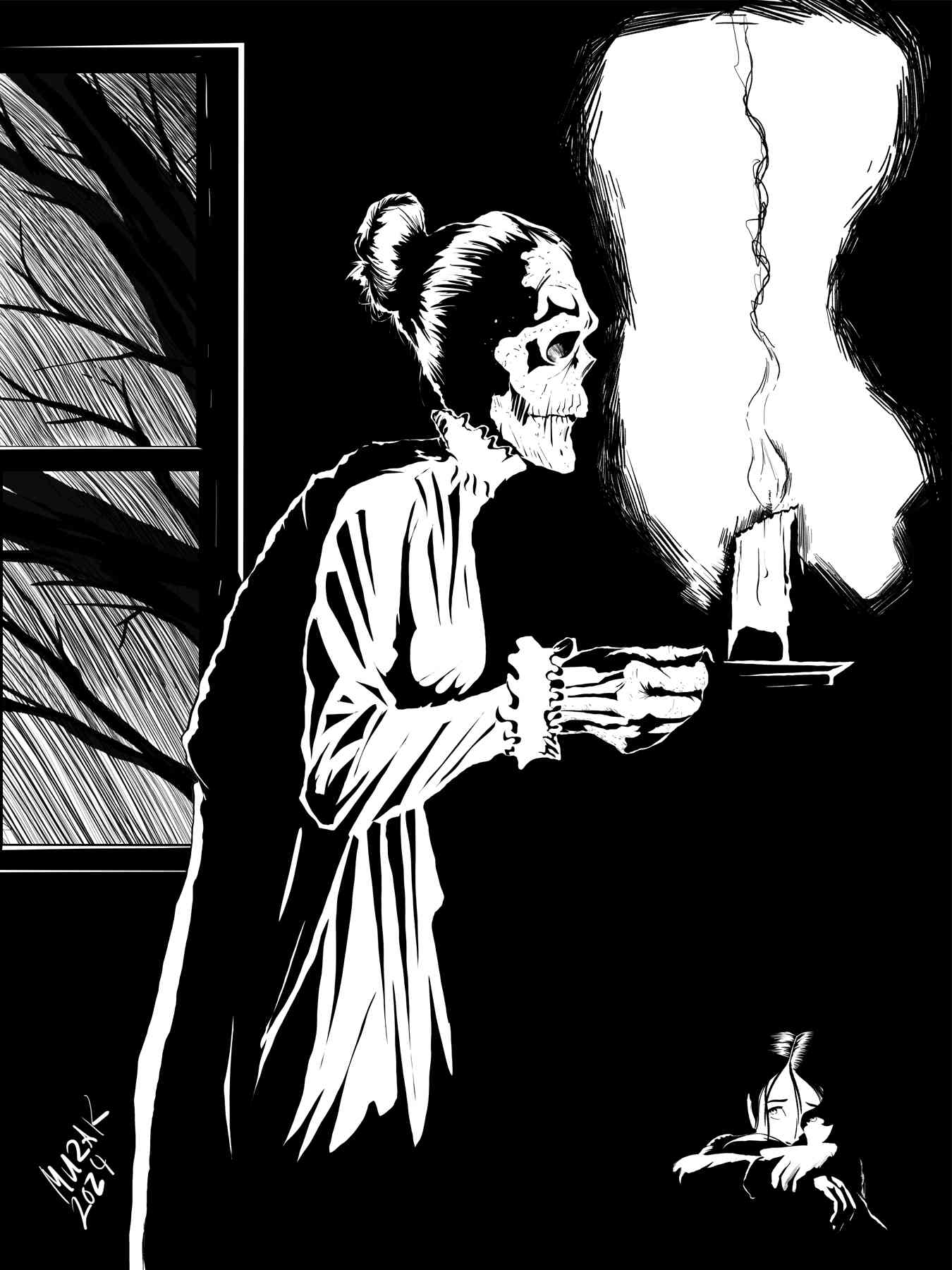

Walking Nightmare by Warren Muzak

Next, Grandad proffers her a scalpel for his big hairy ears. Though she finds it a bit odd, she super glues his ears to the bulky black stereo in the garage. So we can listen to Bob Seger and Taylor Swift on cool summer nights, he explains. The more she takes from Grandad, the more he falls apart. But she cannot disappoint him. She sets his mouth by the billiards table so he can talk smack with the guys. She hangs his nose by a wire in the kitchen so he can smell Grandma’s freshly baked coconut cream pies.

The granddaughter eventually asks her Grandad why he gave her this request instead of her parents, or her cousins, or her Jesus-looking uncle who lives in Utah. You’re smart enough to figure it out, he says. Now here’s a saw for my brain.

After mounting the slimy pink organ by Grandad’s Dime Westerns, placing his liver behind the shelf of half-drunk bourbon, and his lungs beside ashtrays, the girl visits him for the final time. She asks Grandad if he wants her to take his bones or his kidneys, but he doesn’t respond. Within the silence, it’s obvious he has nothing left to give.

The granddaughter grows up and moves to a college out east. She’s dead set on trying new things like lobster rolls and mushrooms from the RA across the hall, but these things come and go. Eventually, her family sells the house where she had dispersed Grandad’s pieces. The new owners ditch the garden, sledgehammer the mantel, break down the billiards table and burn the Dime Westerns. When the granddaughter comes back after so long, she hops the fence while the new owners are asleep and silently paws at the spot where she had buried Grandad’s heart. Though, a dense layer of earth has pushed the heart deeper than what she can dig for. But that’s okay. She smiles and thinks about the artichokes—how the heart is always there, just protected within layers of petals.

About the Author

Jonathan Mann was born and raised in Michigan and is a graduate of Hope College. He is currently pursuing his MFA at Butler University, and his work has been featured in Stoneboat Literary Journal, House of Zolo’s Journal of Speculative Literature, and plain china. He formerly served as the co-fiction editor of Booth and works as an English teacher. You can find him at his website.

About the Artist

Warren Muzak's passion for illustrating started early, captivated by the visual narratives found in comics. He studied Graphic Design in college and from that worked at a few print-shops in pre-press. His abilities creating digital art got him a job as a production artist for a high-end carpet manufacturer where he took beautifully hand-painted gouache artboards and redrew them digitally to be used in manufacturing. In 2016, he met a seasoned UK stop-motion animator while working under contract for a small media production studio. This sparked a new direction—2D animation. Warren embraced it, finding a natural knack and genuine joy in the work and atmosphere in the studio. By 2018, freelancing became his full-time pursuit, honing his craft through persistent bids on online platforms.