By Aimee LaBrie

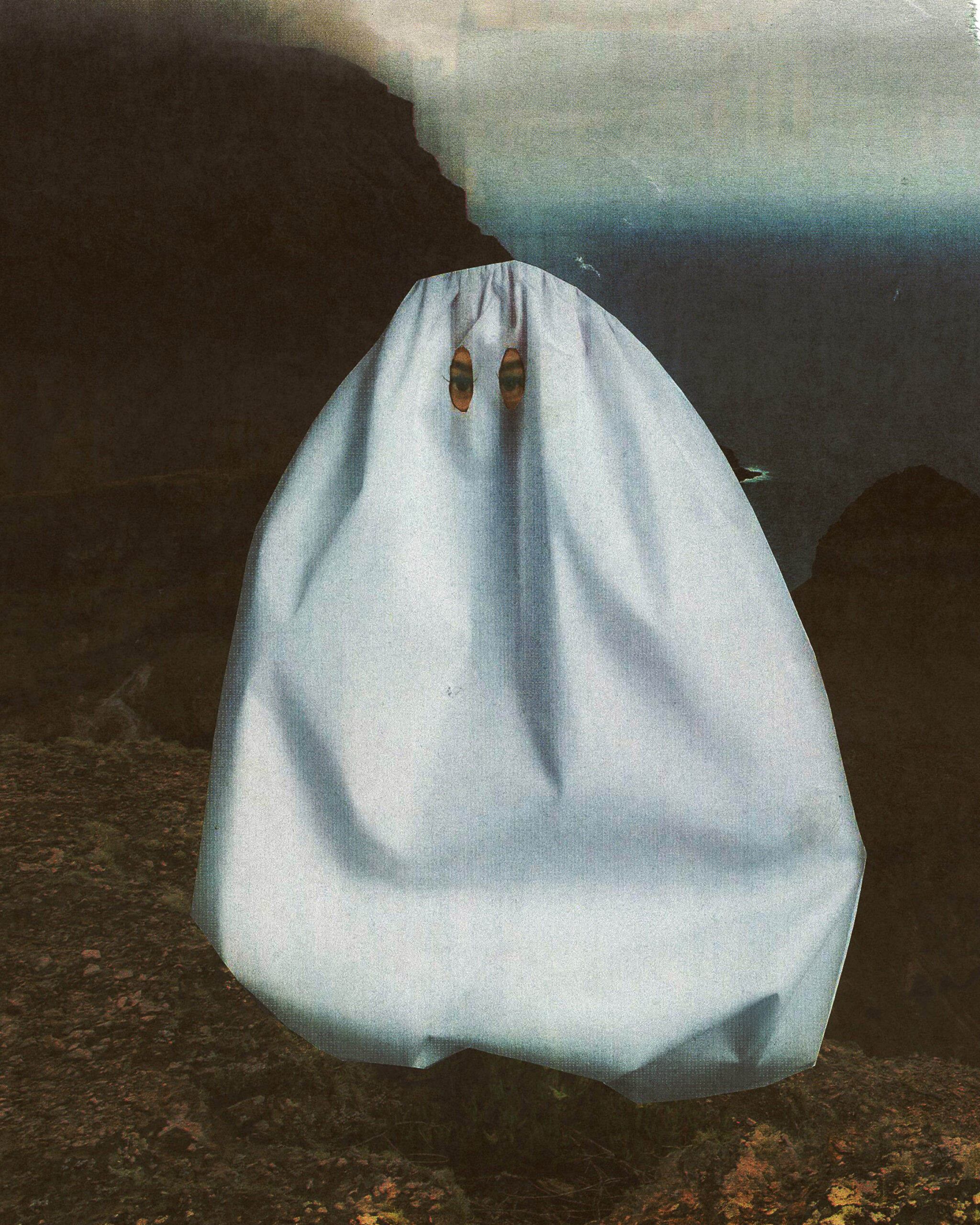

On my way to the doctor’s appointment, I see a man on the SEPTA line, and I know he is wearing Angie’s skin. His face has a certain patchiness to it, raw and pink like salmon where the donor skin has replaced charred flesh. He wears a cap pulled down to hide the marks. I step closer, pretending to read the sign above his head, “See something, Say something.” As a former nurse, I can tell you how long it takes the skin to grow back, can tell you the high probability of skin rejection, can guess he got the burns from an exploding meth pipe.

That is often how I pass my time on the train, diagnosing passengers—the old man with the slight hand tremors is experiencing early Parkinson’s, the woman with the swollen ankles has type 2 diabetes, the pale child listing to the side is anemic.

The burned man is lucky to be alive. Something about his face reminds me of her.

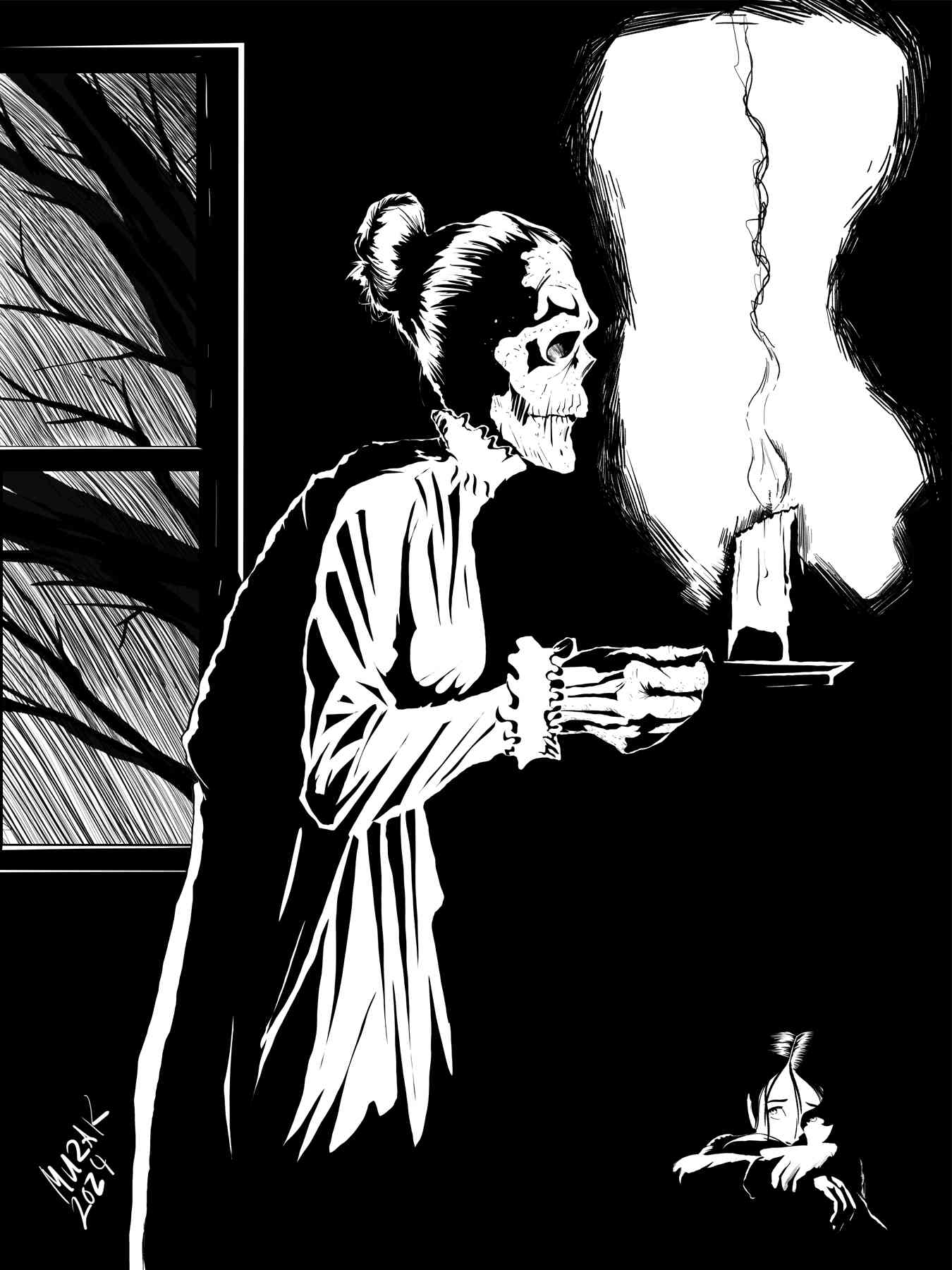

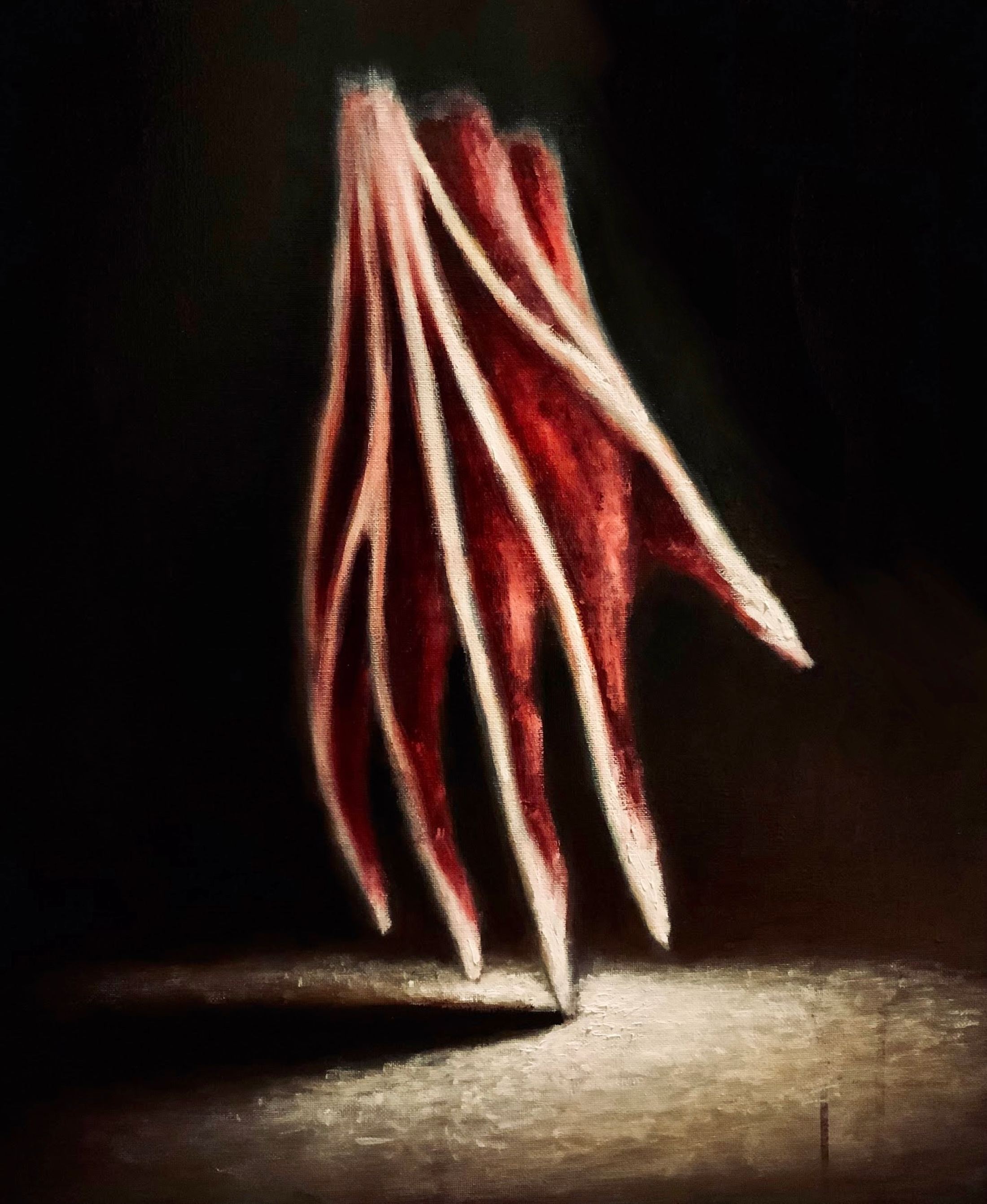

Meat by Michael Katchan

The man looks up from his newspaper and catches me staring. He has no eyebrows. This is a newer transplant, and it looks quilted together, like it hasn’t quite gelled. He takes an inhaler out of his pocket and puts it to his mouth, breathes in.

I turn away, watching the blur of the North Philly landscape through the train window. Abandoned buildings tagged with dark graffiti, rusted out, windowless cars, piles and piles of trash.

She’s in my head now.

Two years ago, I worked as an organ transplant coordinator. My job was to convince families to say yes to donation and then to divvy up the organs to various other bodies. I was very, very good at my job. I could see what people needed to hear to check all the boxes, even as their loved one was on a breathing tube ten feet away. I helped to gather yards and yards of skin, along with bones, corneas, organs, heart valves. I told myself that I did it because I was saving people on the other side, those on the transplant waiting list. But that wasn’t the real reason. The real reason was because I liked the challenge.

All of that changed the night I met Angie.

It was a Tuesday in September, and Angie was my last case for the week. It had been a quiet shift, no slick roads leading to car crashes, no knife fights in South Philly, no one high on ketamine and Nyquil hit by a bus crossing Broad Street. I felt the fogginess of not having had enough sleep. We worked 48 hours in a row, and Angie came at the end of that time. Like most medical professionals, nurses learn how to sleep on their feet, but there is a certain level of tiredness—you may have experienced it yourself when you traveled overseas — the tiredness so present that gives each moment an otherworldly dreaminess. Noises are louder because your body wants to shut down and rest, but you keep moving forward.

Angie Domingo, 16 years old, Hispanic female, blood type O+ the universal donor. Strangled with a bike lock by her boyfriend in the bathroom at Arby’s where they both worked. The boyfriend went home and shot himself in the head with a revolver, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera. He bled out. She was unresponsive at the scene, but the paramedics got her heart back after thirty minutes down.

As soon as I arrived at HUP, I checked her chart, took her vitals, and placed my woolen scarf around her neck so her family wouldn’t have to see the abrasions where the lock had sliced her skin.

While I waited for the next of kin to return, I examined the girl in the bed with her shiny star earrings and wondered what the day before was like for her, whether she had tried to get away from this guy, this manager from Arby’s who was fifteen years older. What did she like about him, this rapist/murderer? Did the two of them have sex in the back freezer where they keep the frozen meat?

You cannot ask the dead body questions. You can investigate the state of the flesh, look for burn marks or cuts or signs of physical or sexual abuse. Those provide clues. There was no social worker assigned to her case, no criminal record to be found, no track marks in the soft crooks of her elbows. On this girl, prior medical records from the pediatric doctor showed that she had a healed broken femur, but no current signs of trauma, other than the ligature marks from the bike lock, and the cuts on her knees when she fell to the tile floor.

The mother and father came into the room. The mother wore a gold cross around her neck. The father clutched a Bible to his chest. They were small, dark haired, polite, eyes red from crying. I shook their hands, told them how sorry I was about what they're going through (lo siento). The mother had a hold of her purse like she worried she would drop it. The father kept wiping his face with a white handkerchief.

I wasn’t sure how much they understood about organ donation or about their daughter’s death. We had already done the brain death tests. The on-call neurologist had done a brain scan when she was admitted, and it came back as flat and clean as you’d like it, no blips of activity. A few hours later, they had done reflex test, sticking a cue tip in her eye to see if there was any small bit of Angie in the back of the mind, screaming to be let out like a locked in syndrome patient in a Twilight Zone episode. There was nothing. From the neck up, she was dead. A vegetable. A nothing. The color in her face, the fact that she looked just like she was sleeping, her moving when I touched her, were because of the machines that kept the heart pumping, the blood flowing, the oxygen moving in and out.

The mother said something I didn’t understand. I had asked for a translator, but it was 3 a.m. and there were none available. She asked the question again, rubbing her hands together, and I took this to mean she was worried that her daughter was cold. A bad sign for me because it meant they thought she was still alive in there somewhere. Angie was brain dead, she felt nothing. She wasn’t cold or hot or lukewarm. She was dead. I nodded anyway and got another blanket. Together, we tucked it around Angie’s body while I searched for a way into the conversation about donation.

I tried to remember the Spanish words for “priest.”

As if she understood, the mother said, “We pray?”

I didn’t want to pray. I wanted to sleep. I imagined what would happen if I lay down next to her daughter at that moment. Instead, I said, “Iglesia?”

She nodded. The husband stayed by the bed, running his fingers over the blue beads of a rosary, lips moving soundlessly.

I walked the mother over to the hospital chapel, a place I had not been in for years, not since I was a little girl living with my grandmother. The chapel had three small pews, an altar, and a place to buy prayer cards. It smelled like incense and roses. It’s where all the flowers went after the patients were discharged or died.

I put in a call to the hospital clergy and then followed the mother inside.

The mother got on her knees. I knelt next to her, my head bent against the velvet of the pew in front of me, and I fell asleep for I don’t know how long. In my half waking and half sleeping, I thought Angie had come in behind me. My neck went wobbly, the hair on my arms pricked up. I imagined she was blowing on the back of my neck, with soft breath that smelled sweet and rotten, like the dying flowers in the vases.

I awoke with a start.

The mother turned to me, patting my arm. “Tired?”

I nodded.

What I remembered from my brief time in the Catholic Church was that the mother might be worried that the daughter had committed a sin. Maybe her daughter had sex with her murderer. Maybe she had been sneaking around. “She was a good girl,” I whispered.

The mother turned to me. She had a wide-open face, a dimple that appeared in her cheek as she gnawed on her lips with worry. “An angel,” I repeated, holding her gaze. “Angel.” The word is the same in Spanish and English.

She nodded slowly, considering.

It didn’t occur to me then that maybe Angie was not an angel—that maybe she was something else. Not a good person, not a bright and shining star.

An hour later, the mother checked all the boxes: cornea, heart, lungs, liver, intestines (small and large) kneecaps. Pancreas, kidney. Skin.

They said yes to it everything. Todos.

As they were leaving the room, the mother turned and grabbed my hand. “Thank you,” she said. Before I could respond, she pulled me into a tight hug.

I felt nothing. Just the quickening of her heart against my chest. “De nada,” I replied, pulling away.

The bones would go to heal shattered kneecaps, the skin to cover burn victims, the lungs to a boy 1,400 away with pulmonary disease, the heart to another person, the kidneys to two more, corneas, etc. Her body would be taken apart and distributed across the country.

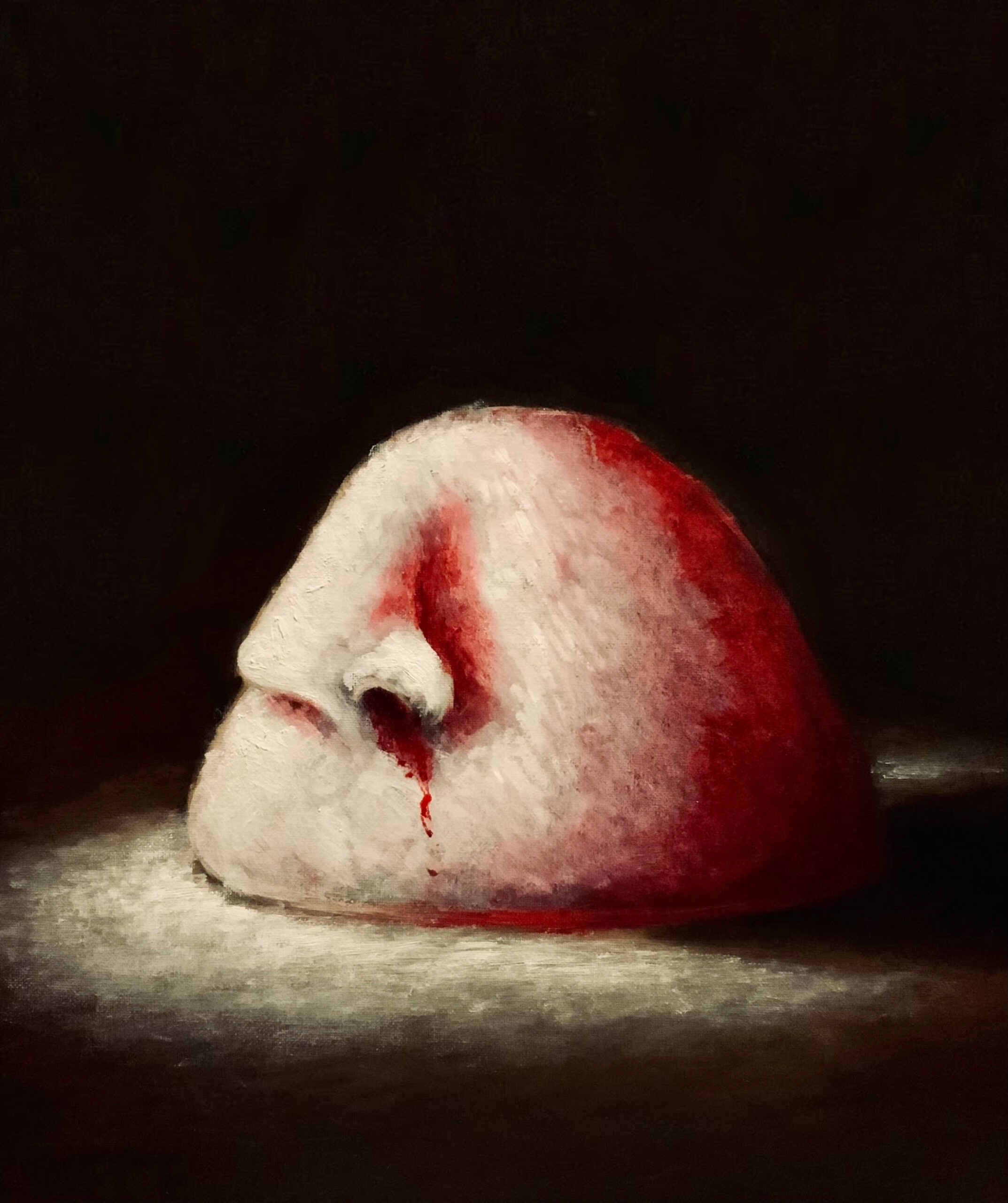

After they left, I was alone with the body. I took Angie’s hand, warm, living, said, “Squeeze if you hear me.” She did not squeeze. I pinched her forearm, hard. The flesh stayed raised, no movement. I pushed the hospital blankets away and grabbed the skin above her thighs. No movement.

Everything after that should have been normal. I’d been through it many, many times. Phone calls to schedule the OR, phone calls to place the organs. Routine bloodwork to make sure we don’t place a diseased kidney into a healthy body.

I took blood from her arm for a second round of tests. Waited. Played a jewel matching game on my phone and chit-chatted with Julie, the night nurse. The second round of bloodwork came back. In donation cases, we must rule out problems. Her blood work was pristine: no cancer, no blood disorders, no HIV, no hepatitis, no traces of narcotics. She was clean, clean, clean, except for one detail: the presence of human chorionic gonadotropin or hCG. Pregnancy hormones. Angie had a tiny, itty bitty collection of cells in her uterus that, if given time, would grow into something more.

I read the results and blinked. My contacts were dry from being awake so long, I didn’t trust that I was reading the report correctly. I looked at the first printout and saw that I had missed it.

Now, a choice. Did I call the family so they could reconsider donation? I didn’t think they would understand—first, because of the language barrier and second, because of the praying, the rosary. I imagined the struggle of trying to convince them she could not survive on machines for the additional eight months required to grow a baby. I had these conversations before without the barrier of a different language. Families who believed they could bring the brain-dead person home on the ventilator and set her up in the living room, surround her with Lady Madonna candles and St. Michaels prayer cards, drape her in blue-beaded rosaries and clean her regularly with holy water.

Angie was never coming back. They would be housing a breathing corpse. The organs would decompose. The baby would miscarry. Brain dead means all the way dead, not sort of dead. She would not recover slowly, heroically, take wobbling steps toward your family. They could put food in her mouth, and it would fall out on the carpet.

But take someone who believes that Jesus died to save them, that believes in drinking the blood every week, and you may find that the rules of medical science do not apply.

I returned to the body. She looked peaceful, eyes shut, dark hair fanned against the pillow. Her mother had insisted on brushing her daughter’s hair before she left. Angie’s star earrings sparkled; her brow was clear. I wondered if maybe Angie had known about the pregnancy, if maybe that was something she told the man who shot her—if maybe he had an opinion about the pregnancy that she didn’t share.

The guidelines from the organ procurement organization ware clear: a brain-dead woman could not consent to keep the baby, and so the woman should not become a human incubator. The baby would not survive anyway. But the family should be told.

I placed my hand on the blanket, near her abdomen.

She jerked. She then sat straight up in the bed and fell back against the pillows. I thought I was hallucinating, but she did it again, her hands clenching and unclenching on the hospital blanket. I put my hand against her chest, feeling the coarse fabric of the hospital gown under my hand. This was normal. It's called posturing. It happens because of an influx of nerves in your body, a twitch of electricity.

My grandmother had chickens, and my earliest experience of them was seeing her walk out into the yard, striding in her solid practical shoes (she was a nurse too), grab the chicken who was too slow or too tame, and lope off its head on the cinderblock in the back yard near the swing set. Headless, the wings flapped in the air while blood sprayed from the pipe of its neck.

Posturing of a patient had never happened to me on a case, but I knew it wasn’t unusual.

That is what I told myself.

Just to be sure, I dislocated her breathing tube. Removing the tube is not against the rules, though it’s the doctor who is supposed to do it, not the nurse. It’s one of the tests for brain death. You take away the oxygen to see if the patient breathes on her own. I waited, counting the seconds on my watch. Ten seconds: no breath. Twenty seconds, nothing. Thirty seconds: no breath. At 35 seconds, she tipped sideways. Her eyes flew open, blank white, like the baby case I had one time, the baby who crawled into the blow-up pool and drowned face down in three inches of water. I looked at Angie’s blank eyes; one was colored bright red where a blood vessel burst. I felt a rush of fear. I moved to put the tube back in her mouth, and her teeth shut with a snap, cutting into my fingers. When I tried to pull my hand out, I couldn't at first, and I panicked, knocking her away from me. My fingers caught on her top teeth, drawing blood. She slumped forward on the bed like a doll, and the heart monitor went crazy, bleeping alarms that meant she was going into cardiac arrest.

Julie and two other night nurses rushed in.

I stepped away from the bed, holding my hand. The pain was sharp, sudden. The cut ran along my index finger, sliced like the gills of a fish. I rushed to the bathroom sink to clean the wound, then added disinfectant and bandaged it up, my hand trembling.

The sound of the heart monitor had stopped clamoring when I returned. “What happened?” The nurse asked, looking at the bandage on my finger.

I said, “I cut myself.”

We got her stabilized, pushed in more meds, and that was the end of it.

While she was in surgery, I returned to the chapel. I knelt on the pew, stiff, awkward, felt like an imposter, put my hands together and tried to pray, but my mind wandered. It was like I was watching myself perform this action from another place. Me, not me.

I looked up at the crucified Jesus on the cross, his eyes heavenward. Then it seemed like his eyes shifted toward me. My vision blurred. I saw his fingers move, the hand with the stake wiggled, as if he were about to pull free. I was sure he would climb down to get me, to take me by the throat with blood on his hands, saying, “You are a murderer.”

I rushed from the chapel, knocking over a vase of dried roses.

In the middle of the surgery, as they were removing her heart, I woke up. Someone had dropped a scalpel, and it hit me in the bottom of my sneaker. I had been asleep on my feet in the back of the room, and thought, Oh, no, oh, wait, I forgot. The priest had called earlier, he said if I waited another hour or two, he would be finished with the baptism of a dying baby. He was in the pediatric wing of another hospital, an hour away.

“No, no, don’t worry about it,” I said. I couldn’t fathom another hour in the room with her. “She’s fine. She’s…it’s okay.”

What can you do? There had been a fire in North Philadelphia, six row homes at one time. Priests were gone, they had to carry the bodies out and bless them with the smell of burning flesh in the air, smoke rising from the buildings. No one was there to help, and that’s just a matter of timing.

I could have waited for him, that is true. But I was so so so so tired.

About the fetus, there is no story. It’s like a Russian doll, one life inside another, inside another. I thought for a second: what if the baby had a baby inside it, and then another baby inside that one, all of them spilling out onto the operating floor, like when you gut an animal and all of the other creatures it has eaten spill out in a slick blur. My dad did this once to a large fish, and a minnow, still flopping alive, came out, a silver flash in the bottom of the boat. I picked it up by the tail and released it, a second chance at life. That’s the slogan we have, if you want to call it a slogan. A second, third, fourth chance of life.

The rest of the surgery went without a hitch, heart, lungs, abdomen, eyes, liver, kidneys to two different people, bones removed from the body and replaced with metal tubes for the viewing. Yards and yards of her skin. All of her taken apart, piece by piece.

One of the doctors, a nice one, followed up with me as I was packing up to go home. He said, “It looks like she was three months.” I pretended not to know what he meant, waiting to see if he was going to be the type of doctor who reported infractions. He had dark circles under his eyes. Like me, he had been working for hours on end. “Didn’t you see the blood work?”

“Yes, I guess I must have missed it.” I was able to say this while looking him straight in the eyes.

He opened his own eyes wide as if to wake himself, then blinked. He had been in surgery for ten hours. “We can use it. The placenta. Do you want to let the parents know?’

I nodded, “I will.”

I did not call the family. Instead, I scrubbed out, put on my clothes, and caught a cab home. I did not say goodbye to the body. The last time I saw Angie, she was under a sheet, her body opened up from sternum to uterus.

For the greater good, you understand.

The train begins to slow. We’re near Kensington Hospital. Dr. Patel waits for me. I get up, glance once more at the man with the borrowed skin, give him a small smile. He doesn’t even look like her. It’s unlikely that a piece of her is attached to him, just like it’s impossible that she was alive when they opened her up and removed her organs.

Yesterday, I received a phone call from my primary care physician. I have been seeing blood in the toilet, wispy red arms of it every time I pee. I knew I wasn’t pregnant, so I prayed for a cyst. Or even a benign tumor. Dr. Patel said, “You need to come in on Monday.”

“I have to work on Monday.”

“You have a family member who you can bring in with you?”

Doctors never say that the news is easy.

The way I picture it is a dark mass, a mess of hair and teeth rolled into a fleshy ball. The medical term for this type of mass is “teratoma.”

When she bit me—that’s when it happened. It went into my blood, that poison from her. That’s what I kept thinking. Whatever darkness she had added to my own dark heart and worked its way into my bloodstream, polluting me too.

In pathology class in nursing school, we learned how to track diseases in your body. Pathology: the causes and effects of disease. Some diseases are genetically inscribed in your chromosomes when you are born. Whether you are likely to get Huntington’s Disease or multiple sclerosis or scleroderma. Other diseases develop on their own. When something is wrong in your body, it is called an abnormal pathology. Some pathology can be changed. Maybe you were prone to bone disease, but you drank a lot of Vitamin D milk. Some pathology can only be uncovered with time.

For Angie, maybe there were genes for depression, ADHD, psychosis, who knows. For me, it could be the same aggressive uterine cancer that took my grandmother and then later my mom’s sister. Both went from diagnosed to sick to dead in under two months. I saw it happen when I was younger, and I’ve been on the outskirts of unexpected deaths in my profession. Cancer varies, but it is not pretty. It is not something I can handle.

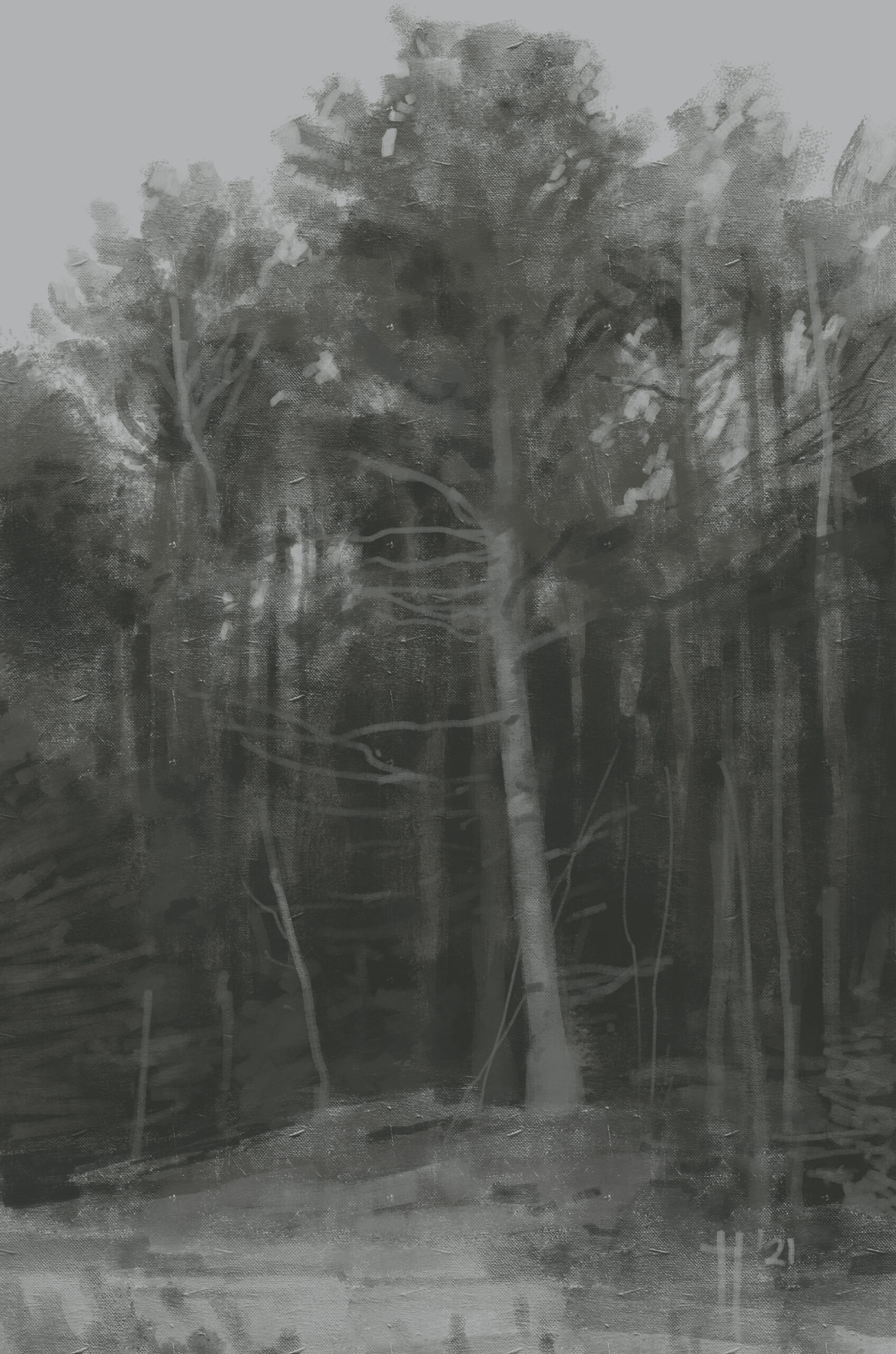

The train brakes screech to a halt, the world outside coming back into focus. I have decided. If the doctor says what I think he will say, I will follow Angie. But it won’t be in a public place. There are plenty of secluded trees in the thick of Wissahickon Park, places where the soil is dark with worms and mushrooms, places where you could take a sturdy rope from Ace Hardware and fling it over a tree branch. I don’t want to be found by a hiker, or a German Shepherd like you see in those detective shows. What have you found, boy? I’d like to stay there, swinging, facing the sun, until my body decomposes, returns to earth. No donation for me, not with all the cancer cells.

I stand up, glance at the man with the patchy face. He has his head down; He wears a pair of blue coveralls and heavy brown work boots. He is an ordinary person going about his day. Not a ghost.

I exit the train car, feeling a sense of dread return to my body at the thought of my appointment. I think, Don’t turn your head, because if I look back and he is watching me, I will know that the doctor has bad news.

The train starts to pull away. I can’t help it. I glance at the man. He is staring down, the brim of his cap shadowing his face. As the train car lurches forward, he looks up. His eyes meet mine, and his mouth opens in a brilliant, toothy smile.

About the Author

Aimee LaBrie’s short stories have appeared in the The Minnesota Review, Iron Horse Literary Review, Cagibi, StoryQuarterly, Cimarron Review, Pleiades, Fractured Lit, Beloit Fiction Journal, Permafrost, and others. Her work has been anthologized in A Darker Shade of Noir: Body Horror by Women, edited by Joyce Carol Oates, and Philadelphia Noir, among others. Her second short story collection, Rage and Other Cages, won the Leapfrog Global Fiction Prize and was published by Leapfrog Press in June 2024. In 2007, her short story collection, Wonderful Girl, was awarded the Katherine Anne Porter Prize in Short Fiction and published by the University of North Texas Press. Her fiction has been nominated five times for the Pushcart Prize.

About the Artist

Michael Katchan is an illustrator in Denmark. He's addicted to coffee.